Ponzi Schemes And Pension Valuation

Monday, 04 March 2013By Con Keating

Market prices reflect fear and greed, telling us about the last disagreement over value, but little or nothing about an asset’s usefulness in meeting future pension payment cash-flows. It was this growing realisation and disquiet, on the part of, among many, the NAPF, CBI and Association of Member Nominated Trustees, that led to the DWP call for evidence on smoothing. The evidence that current accounting and valuation standards produce results that are volatile and biased is now overwhelming. Management of a scheme under these standards is a thankless and expensive task of Sysiphean dimension and Augean substance; disclosures and transparency serve to mislead rather than inform trustees and members.

Some have argued against any form of smoothing on abstract principle. This fails to admit that pension schemes are themselves smoothing mechanisms – they share and average savings, investment and pensions over multiple and extremely long time-periods. It also fails to recognise that the current “mixed attribute” standard of discounted present values for liabilities and market prices for assets itself contains a smoothing mechanism – that is exactly what any discounting process does when reducing future payments to a single present value.

Of course, the accounting and valuation debate is nothing new – it has simmered in the background since its introduction a decade ago. It is the sheer volume of evidence, of its pernicious effects, which is new.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to conclusive resolution of this debate has been the absence of a technique that fully resolves the issues that have been identified. In a recent paper titled "Keep Your Lid On: A Financial Analyst’s View of the Cost and Valuation of DB Pension Provision", prepared for Long Finance and the European Federation of Financial Analysts Societies, this lacuna has been filled.

In this paper, the Internal Growth Rate (IGR) of a pension system is introduced, along with methods that fully meet reporting objectives and management needs. The proposed method is:

- Project Liability Expense Cash-Flows

- Project Asset Income Cash-Flows

- Compare these at the Internal Growth Rate integral to the awards.

Liability projection is standard actuarial routine in scheme valuation; no change is proposed. In order to achieve consistency in comparison, the projected cash-flows from assets, rather than current asset values derived from market prices , are compared with the pension liability projections. The projection of asset cash-flows is well-established in the econometric literature. Comparison of cash-flow projections is the comparison of apples with apples , a basic requirement of any measurement process; not apples with trees as the standards require. We should remember that the largest trees do not necessarily deliver either the most or the best apples.

Comparison of cash-flows also eliminates any prospect of pension schemes being operated as Ponzi schemes; the heart of a Ponzi scheme is that prices will enable continuation until collapse, which cash-flow projection will expose with the absence of the next dividend or coupon, a matter of weeks or months rather than decades. The projection of income and expense also offers us a prime risk management tool – we can observe directly the timing and amounts of shortfalls and surpluses of income relative to expenses.

The key insight of the paper concerns the discount rate at which these income and expense cash-flows are compared. It turns out that there is a natural rate, known as the internal growth rate (IGR), which applies to any scheme, and which is fully determined by the terms of the pension awards. This amounts to no more than requiring that the present value of contributions must equal the present value of the promised pensions . In this, the approach considers an element of scheme design overlooked in current practice, contributions.

The IGR is the implicit or unstated rate of return promised to members on the contributions, given a set of pension expectations. In a book-reserve scheme, it is the cost of the contribution capital to the sponsor. For a funded scheme in deficit, this is the cost of the deficit capital to the employer. This is important; this method informs us directly as to the amount and cost of a deficit to the sponsor, which can only be extracted with great difficulty from current standards and practices. Formally, this is simply a fair value condition.

The fact that this proposed method is fair value consistent demonstrates, through the differences which arise with “market-consistent” approaches, that the current “market-consistent” techniques are not “fair value” consistent – which should trouble the accountants greatly. By considering contributions, the IGR avoids any need for exogenous variables, such as the use of arbitrary rates and prices. This also shows that the Pension Regulator’s claim, that flexibility in the choice of the expected return of assets is sufficient to remedy the problems, is false. That approach will result in liabilities that are misstated and volatility of valuations due to the continued use of market prices for assets. The use of variables (e.g. market prices, gilt yields, choices of asset returns) that are exogenous to the system and do not reflect scheme arrangements and dynamics will always produce erroneous results. The IGR enables accurate and consistent evaluation of the state of the pension system when applied to the income and expense projections. This will go far in restoring trust and confidence in our pensions system.

The IGR is a slowly moving rate, because the real activity in any year is marginal – pensions paid and awards made are typically less than 3% of the scheme’s overall size. It is only with major revisions to contributions or pension expectations that the IGR moves by more than a few basis points. This stability of reporting is complemented by the elimination of spurious external effects in valuations – and quantitative easing surely qualifies as the spurious effect, par excellence, over the lifespan of pension schemes. Changes to the IGR are real and the information in the valuation meaningful. Using this method, it will be possible to avoid unnecessary and costly interventions in scheme management, that are purely aimed at improving reporting under current (misleading) standards rather than on improving fund dynamics.

The estimate of fund IGR may incorporate the entire fund design, including funding arrangements with sponsors and the use of insurance and guarantees; this is not possible under current methods, for example, the market value based approach. The IGR can be used to assess and measure the impact of management interventions, such as liability driven investment and closure of schemes to new participants, and sheds new light on the question of the affordability of DB schemes.

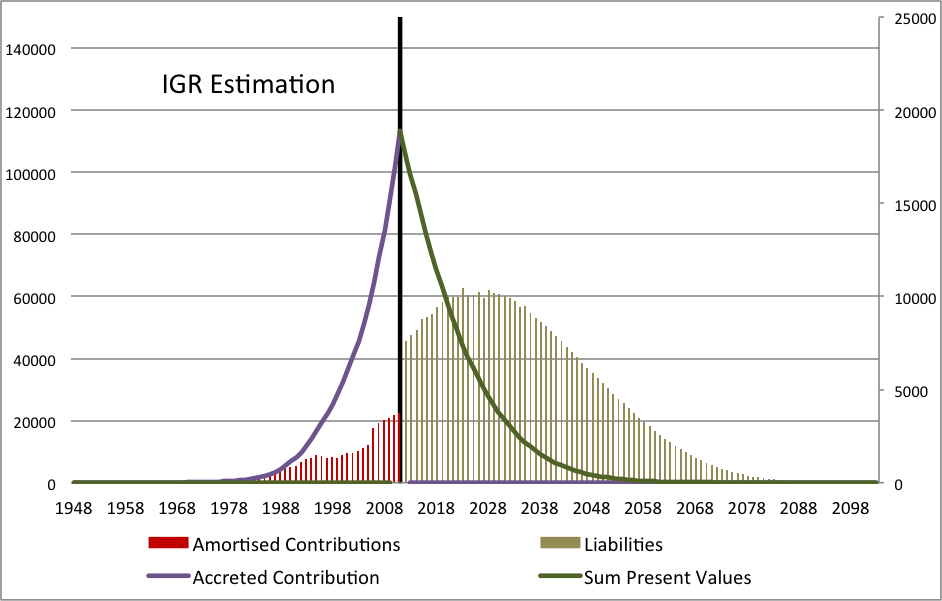

The IGR can be estimated in a number of ways, but the simplest of these is illustrated as Figure 1, which shows the contributions and projected pensions payable and their present values under the IGR.

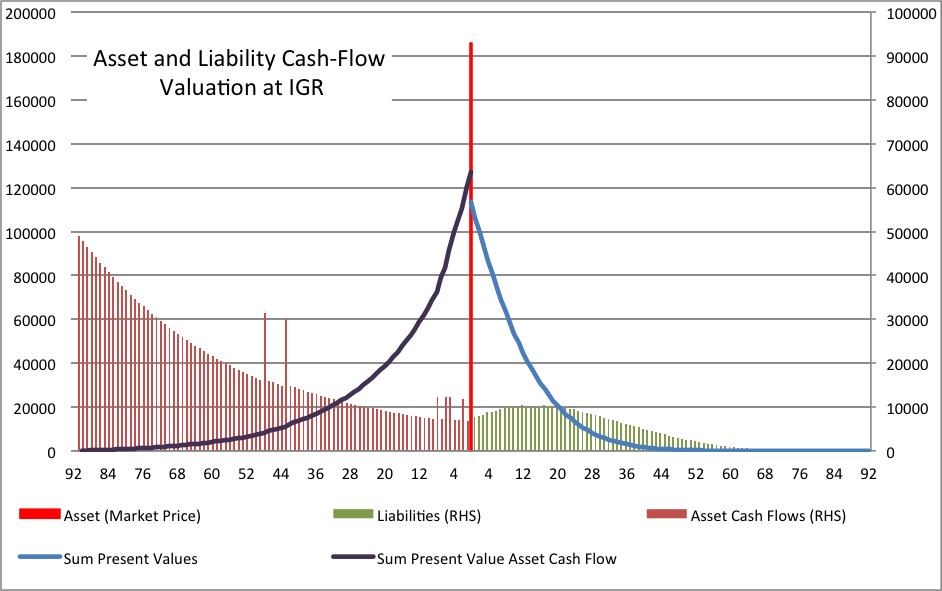

This can then be used as the discount rate at which income and expense cash-flows are compared. The results of this comparison for an illustrative scheme are shown as Figure 2. This figure shows the cash flows arising from the asset portfolio held and the pension expense cash flows. It also shows the current market value of assets at the evaluation date, together with the present values of the income and expense flows.

This figure shows that the present value of projected income flows exceeds the present value of pension expense flows, when both are evaluated at the IGR. In other words, the scheme is solvent having a small surplus. It is notable that the present value of income is far lower than the market price valuation of those assets. This arises because the income yield on assets is currently far lower than the IGR. The corollary to this would be that if the income yield on market assets exceeded the IGR, the value of that income stream would exceed the market value of the assets. This is rarely the case.

The relatively high value of the IGR, which for this illustrative scheme is 7.68%, arises because this is the average rate implicit in awards, many of which were made long ago – they stretch back through time to the 1940s and include periods when inflation and returns were high, notably the 1970s and 1980s. The scheme has a long memory – a product of its intrinsic smoothness.

Some have noted that it might be possible to manipulate the income cash-flow projections. It indeed might be, but such manipulation should show itself in failures to receive income as projected in a matter of months and revisions then be required . The audit process is a simple and immediate one.

Perhaps, the most important thing to realize is that the modeling of asset prices is a hard task, in large part because they are very volatile, but by contrast, the modeling of income flows is relatively simple, since these are an order of magnitude less volatile than prices. Indeed, when an appropriate time serial model is used for income projections, the curse of forward error propagation that bedevils so many asset price models can be entirely eliminated. Such cash flow projection techniques also provide incentives for schemes to invest for the long-term, rather than speculating on short term management success measured by transient prices.

The interpretation of these valuations is simple; they are fair value estimations. The present value equality of contributions to pensions is just that, a fair value condition; in fact, it is the most primitive of all fair value conditions, a precursor to such more complex constructs as arbitrage-free pricing. With market prices so different, we can see that market consistency does not ensure fair value.

However, if we wish to produce figures that are market consistent we need do no more than rescale the surplus (or deficit) by the ratio of asset value at market prices to the value derived under the IGR. Why we should wish to do this is a mystery. The 5/95 confidence intervals for the market consistent evaluation is +/- £74 million for this illustrative scheme, while the equivalent confidence intervals under the IGR is +/- £7 million. It is clear that most of the volatility we currently observe in scheme valuations is an artifact of the manner in which we account for and value them – a self-inflicted wound. This market consistency adjustment ratio is a measure of the value of the income generated by assets at current market prices – it is a fundamental metric of value to a scheme. The current high value indicates that market prices are high and value poor. This is a direct aid to the intuitively correct practice of buying assets when their prices are low and value high.

The proposed method also opens vistas of new risk management techniques that are more effective and efficient that current buffers and “prudent” evaluation.

EIOPA has been proposing that pension schemes should produce holistic balance sheets and we have seen some amazingly complex models developed to address this question. These are unnecessary with this approach. Any deficit produced under the IGR method may be directly inserted into the sponsor balance sheet, where it would displace retained earnings and equity. Moreover, we know the cost of this liability to the sponsor employer – it is the IGR. The comparison of the sponsor’s return on capital with the IGR tells us about the sustainability of a pension situation. In fact, we can immediately do all of the standard asset and debt service coverage evaluations of basic credit analysis. Covenant assessment becomes a trivial process.

This approach also reveals that much of the concern over rising costs in defined benefit pensions is misplaced; the product of poor accounting and vested interests. The illustrative scheme shown here would report a deficit of 17% under IAS 19, when the reality is a surplus of 12% under the proposed method.

Arbitrary periods over which we might smooth asset and liability values may lack any intellectual merit, but would have powerful value as signals of the intention of government to make changes that support the provision of DB pensions. Regulatory self-interest is sufficient to motivate this. Introduction of the approach proposed will decrease the amounts and variability of special contributions and see either an increase in corporate tax receipts or an upsurge in corporate investment. The IGR method proposed is smooth – exactly as smooth as the scheme itself – and that is smoothing over the entire life of the scheme.