Conscious Control of Consciousness - AI

By

Professor Michael Mainelli, Z/Yen Group & Maury Shenk, Ordinary Wisdom

Published by Medium (30 December 2025).

In the hunt for ‘trustworthy AI’, the control of AI requires conscious effort. AI is tough to define, and consciousness is an even slipperier term. But control is something we think we understand. As humans, we particularly like to think we understand behavioural control. We talk of ‘sticks’ and ‘carrots’.

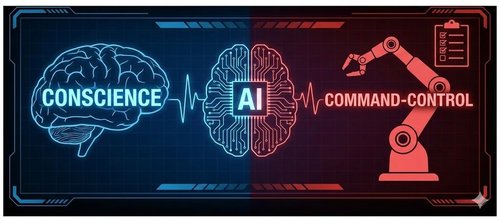

There are at least two types of control – command-control and conscience-control (related to ‘self-control’) . We can control people with objectives and checklists and encourage them to avoid punishment and gain rewards such as bonuses. This is enforced behavioural control. However, we also try to control people’s behaviour through motivation. We encourage them to achieve personal satisfaction by pursuing shared objectives. We appeal to their conscience, asking them to “behave well even when no one is looking”.

Turning to AI, command-control is extrinsic, top-down and outside-in. From the top we impose objectives. From the outside we ‘box in’ an AI system and its performance. Many standardised management systems in finance, risk, operations, the environment, or cybersecurity follow command-control approaches. Such systems are more ‘measurable’ than trying to assess how much each employee is motivated or how much each employee feels like an owner. As the Germans say, “Vertrauen ist gut, aber Controlle ist besser” – “Trust is good, but control is better”.

A good example of command-control is the ISO 42001 international standard for managing AI systems, providing a framework for organisations to develop, implement, and maintain AI responsibly and securely. ISO 42001 helps companies address AI-related risks, ethics, and data privacy by establishing guidelines for governance, risk management, and accountability to ensure AI systems are fair, transparent, and trustworthy. Organisations want to attain the reward of a certificate and keep certification by avoiding non-conformities.

Conscience-control is intrinsic, bottom-up and inside-out. When a coach provides a pep talk to their team at half-time, they are motivating them to perform at their best. They appeal to the reward of personal satisfaction through effort and teamwork. What if we could use conscience-control for behavioural control of AI?

First, let’s be clear that we are not wading into the debate whether AI can be conscious. The latest AI models behave as if they are conscious humans—passing the Turing Test with ease—and in that ‘as if’ there appears to be a sizeable window for application of conscience-control.

Second, control is richer than a dualist command versus conscience dichotomy. In 1986 Gareth Morgan published “Images of Organization” a bestselling book that explored eight metaphors for organisations: (1) machines, (2) organisms, (3) brains, (4) cultures, (5) political systems, (6) psychic prisons, (7) flux and transformation, and (8) instruments of domination. 1, 5, 6, and 8 were biased towards command with a few conscience elements. 2, 3, 4, and 7 were biased towards conscience with a few command elements.

If we are willing to explore AI behavioural control mechanisms that get closer to a balanced view of command and conscience control, how might we go about this? Ordinary Wisdom is a project that aims to see “what happens when a group of humans try to give AI a conscience”. Conscience is the inner sense of right and wrong that guides thoughts and actions – “how you behave even when no one is looking”.

Our basic premises are that AIs need human help in aligning themselves to human values, and that there is no widely-accepted solution for doing this with existing leading AI models. Should people trust dominant technology companies and billionaires to make the decisions on alignment of these increasingly powerful intelligences?

We would take the extensive existing information about good behaviour and ethics and seek to identify principles which most ordinary people would feel should be applied. This might be done by adapting AI models through diverse data-driven simulations, and then rating how those models solve human puzzles and conundrums, particularly ones about ‘right’ or ‘proper’ behaviour. We aim to find ways—which must be both technically robust and grounded in human participation—for coming up with an efficient frontier of behavioural training materials, and methods for applying them to AI models.

The next step could be broader activities and research for using human intelligence to align AI model behaviour, including development of benchmarks for alignment of AIs with human values, and promotion of international standards for such benchmarks.

Conscious control of consciousness needs us to engage both in command-control and conscience-control techniques. Just as AI increasingly challenges concepts of what it means to be human, so too does it challenge what it means for a human to ‘control’ a machine.