A 10 Year Infrastructure Strategy? Or Financial Engineering To Reboot PFI/PPP With Limited Impact?

Friday, 04 July 2025By Thomas Aubrey & Con Keating

When any new government strategy is published, it’s easy to be bamboozled by the government’s good intentions to fix things - alongside big investment numbers that inevitably are referenced to make the strategy look impressive. While governments do generally have good intentions even if they get things wrong, the referenced big numbers are rarely that relevant.

For example, the government claims it is funding at least £725 billion for infrastructure over the next decade. This number seems to be merely the cumulative investment across all departments and regions over time. But what matters for future growth is additional investment. Furthermore, claims beyond what has been allocated in the Spending Review should mostly be ignored as, if the economy does not perform well and there is less inclination to raise taxes, spending may be cut. In addition, future parliaments can overturn such commitments which is the reality of relying on central government funding for projects.

Indeed, one reason why the UK’s investment has been so much lower than most other OECD countries is because of its excessive centralisation of financing investment. This is not the norm across Europe where they invest far more in infrastructure and housing than the UK. This centralisation has enabled the UK government to continually chop and change the spending allocations as the economy is buffeted by external factors.

What ultimately matters though is whether the central financing strategy will improve delivery, and that analysis should be based on practical examples where it has worked either in the UK or in countries that have similar characteristics to the UK. While there are some positive aspects to the Infrastructure Strategy, there are also some serious concerns when it comes to governance, delivery and above all value for money for tax payers.

Let’s start with the positives.

First, the operational reforms across the planning system in the planning and infrastructure bill should deliver a faster, more flexible permissions regime for major infrastructure. In addition, it should reduce delays from Judicial Reviews of major infrastructure.

Second the shift towards integrating physical social infrastructure across different sectors and geographies to address both national and local needs is welcome. The strategy recognises that homes must be connected to water, wastewater, energy, transport and digital networks and that without this infrastructure, the homes that the country needs will not be delivered.

Third there is a recognition that the regulation of private infrastructure including water and electricity needs to change to encourage more investment.

Finally, the government has indeed increased capital investment. March’s Spring Statement indicated the government would invest an additional £2bn per year on top of the £20bn per year allocated in the Autumn budget over the next five years. In addition, the government has developed its Financial Transaction Control Framework (FTCF) with the aim of leveraging public expenditure to crowd in private capital. However, given the scale of the infrastructure deficit, which according to EY, is a shortfall of over £700bn the additional investment is unlikely to be as transformative as it appears.

This is where the positives end. The report remains weak on a number of important areas.

First, its response to criticism by the National Audit Office (NAO) that Whitehall has a governance problem appears to be additional bureaucratic oversight. The proposed solution in the Strategy is to embed the newly formed National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority (NISTA) into projects “to provide enhanced assurance” which “will complement departmental control”. This is alongside “implementing a bespoke approach to governance and funding for current and future mega projects” set out by the Office for Value for Money. But this approach ignores one of the most important principles in improving governance, which is that the delivery body must also be responsible for funding - typically referred to as ‘skin in the game’. An additional governance layer can be introduced by the delivery body financing directly from the capital market as investors will constantly assess progress and risk, with market prices signalling concerns, anticipating success or failure.

Instead, the government continues to rely on centralised financing for delivery agents who have limited skin in the game and who effectively utilise the OPM principle (other people’s money), which is not widely recognised as a driver of good governance. Indeed, poor delivery is one reason why the UK public finances are under so much pressure as so much public money is wasted as continues to be amply demonstrated by HS2.

Second while the intention of the Strategy is to integrate transport with housing, the allocation of the £15.6 bn transport investment was not closely integrated with housing. Hence housing becomes a potential additional benefit rather than a fully integrated component. So there needs to be a much better alignment of theory and practice.

This leads on to the biggest issue with the Strategy which is the financing of projects. While the government rightly recognises the essential role of private capital and the need to attract investment, the government seems to think its issues can be resolved if they can use public money to support private capital or what it calls a public private partnership (PPP). In essence, what the Labour government is doing is reviving the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) approach to investment. The PFI was closed down by the Conservative Government in 2018 as not being of sufficient value for money for taxpayers following severe NAO criticism.

The NAO’s recent report which synthesises prior learnings from PFI projects notes that the OECD “found no evidence of higher quality infrastructure being delivered in advanced OECD economies by using private finance as against public procurement.” Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) are usually delivered on-time and on-budget - but the costs are significantly higher.

This is because private finance is more expensive than public finance as investors expect to earn a premium for the risk taken. The NAO cautions the government to “consider how the risks and gains of investments can be shared equitably with private investors,” as private investors have received returns as high as 30% per annum. Despite the overall risk for investors on PPP projects being low, they deliver typical returns around 9% pa.

The risk is low because the government does most of the derisking as project revenues are based on the availability of assets and the government underwrites the payment. In essence, the government derisks the project thereby enabling investors to meet their profit thresholds For example, the NAO noted in its review of the Thames Tideway Tunnel that there are significant risks on the taxpayer if it goes into administration. Inevitably, some privately financed projects may fail which is why they are a contingent liability. This leads on to the important point on fiscal illusion and financial engineering of the government balance sheet.

Most private finance projects have been off balance sheet and hence are not included in the public sector finance statistics and therefore do not impact the fiscal rule. The NAO recommends the government to make decisions based on commercial and operational objectives, rather than using accounting classifications as a way to get round fiscal rules. Shifting immediate costs off balance sheet and committing public funds to long-term obligations “can obscure the future impact of government-funded PPP projects”, and often the government department ends up with a far more expensive project which is why many government departments have attempted to get out of their existing PFI contracts.

Although it is plausible that new PPP projects could work for smaller scale or discrete projects, it’s hard to see how this might work for say new urban extensions and the necessary infrastructure required to unlock large amounts of housing - a challenge that the New Towns Taskforce is currently grappling with. Indeed, the NAO has noted that between 1992 and 2018 when PFI operated, it only ever financed about 10% of the infrastructure – hence it is just not a scalable solution. The government’s own numbers indicate that this new PPP grounded in the FTCF will provide only limited additional investment.

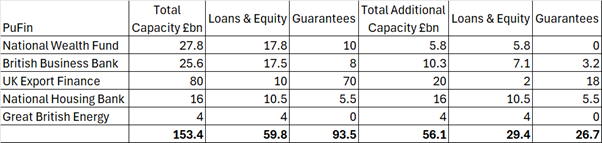

Financial Transactions (FTs) are described by the Government in the following way: FTs allow government to invest alongside the private sector, through equity investments, loans and guarantees. The five public financial institutions authorised are the National Wealth Fund, British Business Bank, UK Export Finance, National Housing Bank and Great British Energy. The financial capacity of these institutions is shown below which is taken from Table 2.1 in the 10 Year Strategy. Although the Strategy provides an additional capacity of £56bn over the next five years, the recent Spending Review forecasts that this will only result in an additional £26bn over the next five years, where an “appropriate risk-transfer can be achieved and value for money.”

Table 1: Public Financial Institutions Capacity

An additional £26bn of capital investment is unlikely to generate much more than an additional £26bn from the private sector given that the FTCF is expected to be utilised only in cases where there is a market failure. Hence the leverage effects are unlikely to be that significant – assuming that the projects actually met the necessary criteria. This situation will be further complicated by the new Industrial Strategy and the demands of private sector investment.

If PPP / PFI projects are not scalable, the government needs to ask itself why is it betting on this approach? There is very little evidence there is a paucity of capital. What the UK has consistently lacked are good-quality, local and regional projects that generate a positive real return on capital. And this is largely because we don’t integrate our projects across the built environment and exploit funding sources such as land value capture. Instead the UK remains wedded to its overcentralised model of handing out grants.

In addition, the UK has diverged from internationally recognised accounting standards that were designed as part of the Maastricht criteria for eurozone governments to maintain fiscal discipline while supporting growth. This divergence means that where UK public corporations can self-fund their projects from private capital, they are considered to be on-balance sheet and therefore impact the fiscal rules - whereas in Europe they are rightly considered off-balance sheet. The reason why self-funded public corporation liabilities are considered off balance sheet is that they are a contingent liability – exactly the same as a PPP.

The UK treatment of public corporation contingent liabilities being on-balance sheet while PPP contingent liabilities are off-balance sheet is not only an inconsistent treatment of the recognised accounting rules, but it crucially constrains growth.

A comparison of the market funded contingent liabilities which is related to investment (as these liabilities have created assets) between the UK and France, Germany and the Netherlands is revealing. France, Germany and the Netherlands have many public corporations that issue debt for specific projects and are paid back by market sources of revenue, not taxation. This includes the debt of development banks such as BNG in the Netherlands and KfW in Germany which often provide long term infrastructure loans for projects. These banks fund themselves via the capital market. They are not funded by tax payers.

France, Germany and the Netherlands have market funded liabilities of between 68% -87% of GDP that in turn drives investment and growth without recourse to tax payers, and thereby reduces pressure on the public finances. In the UK, the liabilities are much lower at 33%, so just under half that of France. But this figure is largely a function of Nat West Group which at the time was deemed to be under public control. Without Nat West, the figure is just 2%.[1]

Table 2: Comparison of market-funded liabilities of public corporations

In essence, one of the most tried and tested ways of funding infrastructure investment to drive growth without placing additional pressures on tax payers and the public finances has been shut off for the UK. It is hard to fathom why the Treasury has gone down this route. Perhaps they believe that the European fiscal rules as set out in the Maastricht Criteria are reckless? But these fiscal rules were largely drawn up by the Bundesbank, and it would be hard to argue that the Bundesbank is a paragon of fiscal recklessness. Besides creating rules for the public finances, the other central pillar of the German social market economy is growth and the prioritisation of investment. This is what the Bundesbank successfully achieved in these rules, and the UK has subsequently rejected.

The decision by the Treasury to move these liabilities on-balance sheet is akin to making a unilateral decision for the UK banking system to have twice the capital requirements of European banks. This will constrain growth as banks will lend less. The data above indicates the UK has become an international accounting pariah of its own making, and one that deliberately constrains growth.

This low level of investment led the Treasury to develop the Financial Transactions Control Framework - which is largely a financial engineering tool to get around the problem of on-balance sheet classification that the government created by its unilateral decision on accounting standards. As described in Table 1, the Treasury has enabled government bodies to create financial transactions (FTs) - which must be backed by allocated departmental capital expenditure limits. The idea is to use these FTs to support its PPP and provide capital that in effect is matched by the private sector. The creation of the new fiscal rule (PSNFL) permits the Financial Transaction to come on balance sheet net of its liabilities, thereby placing less pressure on the fiscal rule. This looks a lot like financial engineering that is merely creating a fiscal illusion.

On the one hand as noted above, some limited additional investment is likely to come out of this financial engineering, but the scale of this investment is still constrained by existing departmental capital expenditure limits. So it will not be that transformational, and won’t be particularly useful when it comes to financing the next wave of new towns and urban extensions. These projects require large amounts of infrastructure to be installed upfront and the existing departmental capital expenditure limits will not enable this. This is why the last Conservative Government started pursuing the land value capture model as a strategy thereby accessing up to an additional £10bn per annum for infrastructure funding, unlocking new land for housing.

This strategy culminated in the transformational changes in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023 enabling development corporations to acquire land at values close to use value thereby enabling the successful new towns funding model. Development Corporations would in effect become public corporations that pay back their liabilities using hypothecated cash flows, and hence are a contingent liability – the same as PPP – assuming the UK decided to become compliant with internationally recognised accounting standards.

Alas, the Labour government appears to have rejected this policy, which is odd given it is the basis for the successful urban redevelopment across Europe over the last 50 years, as well as garden cities and new towns in the UK. Furthermore, this approach could have funded the East West Railway. But instead we are loading the tax payer with future liabilities, which will of course constrain growth.

Why the Labour government is so against public corporations raising debt using identified future cash flows to pay back private investors which is the model the Victorians used, is curious. Indeed, if the current Treasury rules were imposed on Victorian England then none of that infrastructure would have been built!

The chancellor could have unleashed billions in investment for large-scale urban extensions led by public corporations financed by private capital and funded by market agents by following internationally recognized accounting standards. Instead the government will continue with its centralized model of infrastructure investment via gilt financing which will not only curtail growth but will also place greater pressure on the public finances -alongside some clever financial engineering for good measure.

[1] It is worth noting that the Germany figure is somewhat inflated by its public sector banking system