A Tale Of Two Middle Classes

Tuesday, 21 August 2018By Patricia Lustig & Gill Ringland

Here is a puzzle: the headlines suggest that the middle class in Asia is becoming a force to be reckoned with, and the middle class in the northern, mature economies is hollowing out. What is actually happening here?

Is it that middle class jobs are moving from developed economies to Asia? Obviously there has been significant outsourcing of supply chains and back office services to Asia and elsewhere over the last 30 years. However, the current phenomenon seems to us to be qualitatively different.

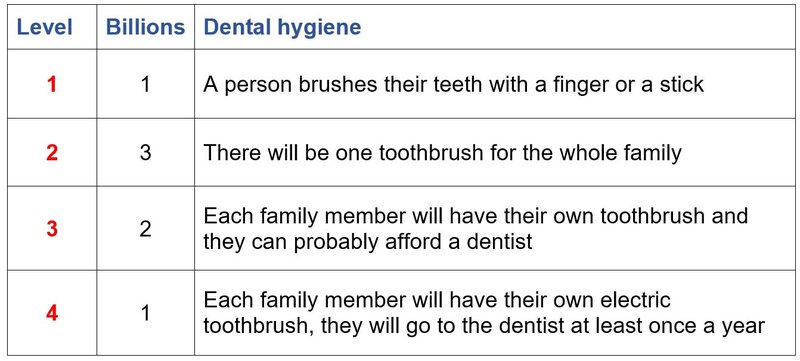

People have a perception of Asian (and evolving) economies that is not aligned with the evidence. To unpick this, we use the UN terminology popularised by Hans Rosling as Levels 1, 2, 3 and 4, for people’s living standards. A quick aide memoire for the living standards of each Level is:

Levels 3 and 4 are often referred to as “middle class”.

Today there are 3 billion “middle class” globally.

In the discussion below, we use the term ‘mature’ economy to refer to economies in countries where the population is stable or falling, the size of the work force is falling, the literacy rate is high, and whose economies have lower growth rates. We use the term ‘evolving’ economy to refer to economies in countries where the population is rising, as is the size of the work force, the literacy rate is rising, and the economy is growing faster than in mature economies.

Currently 60% of Level 4 people live in the mature economies; by 2040 60% will live in evolving economies.

People at Level 4 have more in common globally with other people with level 4 lifestyles than with lower levels in their own countries.

Meanwhile, Level 2 lifestyles persist within mature economies and inequality within countries is increasing.

The rise of the middle class in Asia is largely due to the economic activity of Asians, manufacturing and selling goods and services to industries and consumers largely in Asia.

The age profile in many parts of Asia (but not all, China and Japan are over this bulge) means that large numbers of young people are entering the growing workforce, setting up new households and buying furnishings and consumer goods. This drives demand and creates new industries. Many of these people have migrated to, or have families who already live in, urban areas. This is linked with smaller family sizes and higher female literacy. So, more and more people aspire to and attain levels 3 and 4 in these economies, increasing the numbers of consumers (i.e. people who are able to buy goods and services).

Once people have a Level 3 lifestyle, they start to travel for fun – maybe as well as for work. Initially in country and then when they reach a Level 4 income, internationally. First by motorbike or train, thereafter, often by private car or air. Purchasing insurance and financial services is likely to follow, and soon after they may become interested in pollution and protecting the environment (for their children and grandchildren).

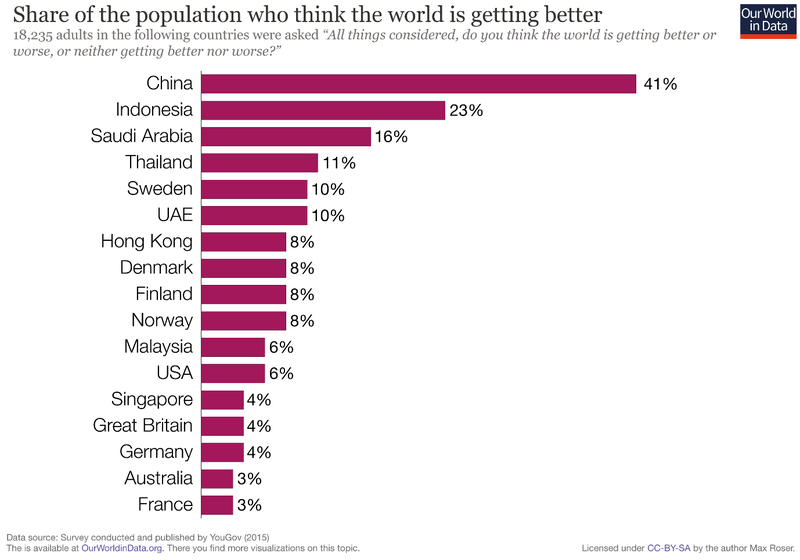

Another differentiating factor between the evolving Asian economies vs mature economies is the rate of innovation. As we illustrate in Lustig & Ringland (2018)[1], the research activity and patents filed in key areas such as artificial intelligence by China is now in the same league as those from the US. In financial services, platforms such as Alibaba and services such as M-Pesa are bringing financial empowerment to people in new ways. And, in evolving economies people are more likely to think that the world is getting better.

These two factors are starkly different in mature economies:

- Demographics of little or no growth in the workforce, a static or declining and aging population with increased dependency factors mean that the traditional drivers of employment – new household formation – are absent. People already have stuff and often don’t need or want more. They may switch their spending to personal services and travel, but these industries do not often provide Level 4 incomes for most employees.

- The long period of stability and growth since WWII has meant that many instruments of investment and innovation seem to have lost their focus, and the innovation pipeline has decayed, with the impact on patents etc in key areas as described above. An older population may also be more conservative and less open to new ideas, meaning a potentially less helpful home market for innovation.

In summary, the middle class in mature economies may lose comparative wealth and global percentage through to 2040, compared particularly with the middle class in Asia and other evolving economies. But this is not only the result of outsourcing of jobs, rather of different economic fundamentals at work.

What does this mean?

Questions to ask any organisations that you are advising (on economic and monetary matters) are:

- What is the opportunity from the changing expenditure patterns of the new middle classes in Asia (e.g. people are only interested in insurance when they have enough to insure): what do you need to do differently to create opportunity here?

- What might the profile (Level 1/2/3/4) and job mix be in a mature economy in 2030? 2040? What is the implication for your organisation?

- What new types of financial services will originate in Asia (or Africa) and be taken up in mature economies? What will the impact be on existing systems?

This Tale of Two Middle Classes is ongoing; it hasn’t finished yet, so it is worth watching. Thomas Piketty in his recent book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, says that the middle class is an anomaly that has existed for a short period of time and is now disappearing with the rise in inequality and that this is an inevitable outcome of free market capitalism.

Does this hold true for both types of economy, what we are calling mature and evolving? Will it hold true going forward?

Does this growth in the middle class in Asia challenge Piketty’s premise? Will this growth of the middle classes in Asia be short-lived? Or might it emerge differently and how might that look?

What could be the impact of Schwab’s 4th industrial revolution?

We are curious and think it is a fascinating time to be alive!

[1] Lustig, P and Ringland, G., Megatrends and How to Survive Them: preparing for 2032, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, October 2018. See www.lasa-insight.com for more information.

Patricia Lustig is Managing Director, LASA Insight and SAMI Associate, and Gill Ringland is SAMI Emeritus Fellow and Director, Ethical Reading