The Church And Crown In Parliament - A Lesson In Mutuality

Wednesday, 17 May 2023By Sam Whimster

For all its touted ecumenical credentials, the coronation service of Charles III was a jarring reminder of Protestant succession, and a throwback to the time of William III and, less so, Mary. All I remember about the last one was people shouting vivat regina, which seemed an odd thing to be doing in a church - but down in Coulsdon we obviously weren't up to speed.

This time, after Archbishop Welby had performed the coronation service with exemplary drive, he popped up on the TV again on Wednesday to speak against the government's Illegal Immigration Bill. He brought to the attention of the House of Lords the central message of the gospels, love thy neighbour.

Government ministers were not amused, suggesting the archbishop should be devising alternative solutions to the small boats coming across the Channel. I am pretty sure that would be mission creep - the Archbishop recognised that souls were imperilled and that it was his duty to point out the universality of Christian love.

Government ministers have limitless powers (give or take some actuation problems) because the executive is the crown in parliament and sovereign. This is not a relic of the late 17th century but constitutional doctrine. The Lords spiritual - the bishops - are there to defend the Protestant faith in its Anglican guise. Commentators seemed agog that on a Saturday the church was revering and anointing the head of state and on Wednesday criticising a government bill. Should this surprise us? It should not, because that is how the two houses of parliament were instituted. Unlike appointed peers, the majority of whom are whipped, the lords spiritual have the right to raise substantive moral objections to the secular executive.

Usually the bishops are ignored by government and the media, but in this episode there was a wider resonance. Those brought up in the Anglican tradition have had drummed into them the social message of the gospels. But then Britain is no longer a majority Church going population, so why did the Archbishop's words cut through to even the average conscience?

Perhaps one answer is the necessity and continuity of secular ethics. Love thy neighbour is the religious version of the neighbourhood ethic. In a time of insecurity - a permanent condition from which the desert religions sprung - an ethic of reciprocity, a neighbourhood ethic was a key to survival.

Plagues, drought and famine could strike down the farmer or peasant indiscriminately. What happened to your neighbour could well happen to you further down the road. Magical formulae and incantations might fortify the psyche, but rebuilding houses and restoring wells and irrigation were basic to communal survival. Mutuality predates the inflation of religious revelation.

The psychological factor today is insecurity, even within the sceptred isle. A major European war is underway with, thanks to modern ordinance, appalling casualties. Missiles fall randomly on civilian housing. The refugee crisis is all too understandable. The climate emergency likewise cannot be ignored. Distress is no longer other people, it could come to your doorstep. Citizens look to the state for re-assurance yet trust in government is at an all-time low.

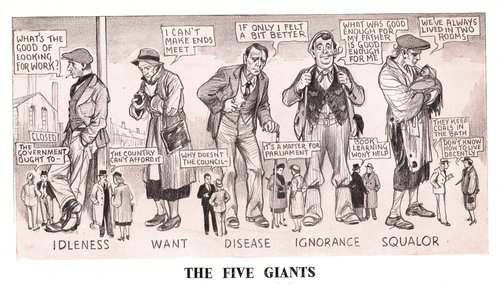

This was not the case when the Beveridge Report was published in 1942 and sold half a million copies. It raised mutuality to the level of a nation on the basis of an insurance scheme into which everyone paid and everyone could benefit from.

Unemployment, poverty, old age and sickness are the civilian vicissitudes, then and now. Beveridge created a secular form of universalism whose impact, and popularity, was immense. Beveridge himself, who worked in the interstices of civil services departments in putting together his report, did not anticipate the enthusiasm it released - that of secular hope.

Beveridge belonged in the tradition of liberal individualism, allowing entrepreneurialism and self-help to flourish once the crushing anxieties were removed by the state, which itself would be an impersonal machine in the operation of the scheme. It was Archbishop Temple of York who declaimed the underlying mutuality ethic be renaming the scheme the welfare state. Was this revelatory inflation of a scheme designed to run on the accountancy of insurance?

Labour Party politicians at the national level saw the Beveridge reforms as a way of achieving socialism aided by the convictions of Christian socialism. The equally long tradition of laissez faire, to go back to David Ricardo's critique of Speenhamland - the obligation of the parish to support the poor - has been relentless in the acclamation of the sovereign individual devoid of ties. Frances Piven and Richard Cloward in the US, from a socialist stance, argued that welfare was a way of regulating the poor, and in this light there is a continuity from Speenhamland to tax credits for those in work. Though a Liberal and in liberating the citizen, Beveridge assumed a number of conditions be fulfilled by the state. In his 1944 Full Employment in a Free Society he assumed a legal minimum wage, compulsory training schemes, price controls, the limitation of free collective bargaining and the extension of public ownership over land. The state should guarantee essential services and – if required – take over private enterprise. Strangely, (in the sense of “how did it come to this?”), it is the essential services that are now failing everywhere.

What can be rescued for mutuality from these competing standpoints? Starting at the top, the central state remains the holder of the social insurance fund, even though it has long since been folded into the Treasury's consolidated fund. The latter has immense firepower to step in as emergency relief, as we've seen with Covid and energy bills. The Treasury, though, as an omnium gatherum of all taxes and contributions loses the acuity of the insurance principle. Unlike the friendly societies where payments in and payments out followed transparent rules of equity, charity and accountability, who gets what from central government - not just citizens but businesses, agencies, and sub-central government - is discretionary on ministers and distinctly murky.

The state needs to build back capacity, something the United States has realised big time. Then, as Michael Mainelli and Lord Toby Harris have argued in a submission to National Preparedness Committee (Oct. 2021), the state can craft permanent solutions at low expense for low frequency but high-cost disasters. The state as insurance-Re. It should also be recalled that Anthony Giddens promoted in his Third Way what could be termed smart welfare. Health risks are as calculable as actuarial tables. They can be predicted and the citizen's own body becomes the object of care. Giddens used smoking as a main example, obesity and food standards are ours.

Coming down a level, fiscal federalism is now widely adopted in most OECD countries, but the UK is an outlier; how stubborn an outlier we await to see, since many are advocating devolving the delivery of social, health and educational services to the local level. Add in to this, the local raising of taxes - sales, property, tourist taxes - and mutuality is glimpsed again. The trade unions, which had their own mutual friendly society schemes, were opposed to Beveridge. They argued a social insurance fund should be controlled by its members, which is the smaller, local and feasible option. More of an occupational ethic, but let's not forget the neighbourhood ethic.

Sam Whimster is Professor in the Global Policy Institute, at Coventry University London.