The Jealousy Of Trade

Wednesday, 07 May 2025By Sam Whimster

Nothing is more usual, among states which have made some advances in commerce, than to look on the progress of their neighbours with a suspicious eye, to consider all trading states as their rivals, and to suppose that it is impossible for any of them to flourish, but at their expence. In opposition to this narrow and malignant opinion, I will venture to assert, that the encrease of riches and commerce in any one nation, instead of hurting, commonly promotes the riches and commerce of all its neighbours; and that a state can scarcely carry its trade and industry very far, where all the surrounding states are buried in ignorance, sloth, and barbarism. (David Hume, ‘Jealousy of Trade’)

The Scotsman, David Hume penned this critique of the protection of trade in 1758. The better known and later critique is by the political economist David Ricardo which was penned early in the nineteenth century. His was an economist’s arithmetic proof of the benefits of each nation producing what they are best at, and trading with other nations for the goods they were less successful at producing. Ricardo’s proof is reproduced, as the theory of relative comparative advantage, in every economic textbook and is the basis for arguing for an international division of labour. Hume’s argument is also in favour of an international division of labour but is made from the view that a leading nation can drive up the overall level of civilization. His argument relates to the social division of labour and the fostering of arts and trades, and it is made as a social philosopher, not as an economist.

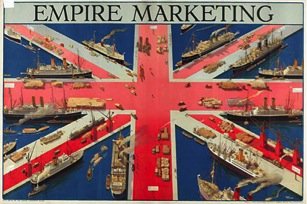

Hume and his fellow Scotsmen had a ringside seat as England embarked on global economic expansion and the aggrandizement of colonies. Scotland was a small nation, part of Great Britain since 1707, and the Scottish philosophers took a more reflective attitude to England’s gung-ho policies. Hume reflected on a new circumstance: commerce and international trade had met the emerging representative state. Trade had become an affair of state, the Board of Trade consolidating itself as a permanent office throughout the eighteenth century with its major function being the administration of N. American colonies. A closed dynastic state jealous of its monopolies and insistent on its custom posts was superseded by a state that was more representative in its institutions, and that its power, vis-à-vis other states, was greatly dependent on its trade abroad and commerce at home. For Hume, the moral imperative was to steer the new commercial state away from war and to realize in commerce a force that, crucially, stood for the conditions of liberty. Scots were, at the same time, struck that the liberty and commerce enjoyed by Great Britain was not extended to Ireland, finding the jealousy of a rich overlord of a poor nation obnoxious, not least the forced migration of the Irish.

For the second Trump administration there is no neighbours, only the aggrandizement of land and other countries. Also, all rival economic powers are enemies. Those countries of the world still way behind in acceptable standards of civilization are to be cut off and left to their fate, burdened with impossible trading conditions. The civilizational advantages of trade are to be turned into their opposite, and the restriction of commerce becomes the curtailment of liberty. How the modern republic flourished through commerce has come to a juddering halt.

These harms are executed as reasons of state. The primacy of commerce, in the form of repatriating all manufacturing within the United States, is switched so that open government is replaced by dictatorial executive rule and the closed economy. This situation goes far beyond an ignorance of neoclassical economics and into the malignancy of the state, which the twentieth century has shown to be only too feasible. The philosophical voice of the Scottish enlightenment, prior to modern economics, is the inquiring voice of a humanist political economy, in contrast to the univocalism of aggregate economic wealth.

The economists’ argument for the benefits of trade are in a technical sense, as deployed by the ‘late’ WTO, capable of rectifying the situation. In the full blast of Trump’s tariff war, a long de-escalation drawing in all aspects of protectionism could perhaps return the world to a better place, even an improved status quo ante. That would be the best bet for commercial statecraft. But David Hume and his fellow Scots set up the arguments for state and society as a commonwealth and how commerce was key to its dynamic. This analysis was never sufficiently carried through; nor the recognition that the analysis belonged to the philosophers, not to the rationalist technicians.

Economists and trade officials can supervise trade negotiations and achieve narrow political outcomes. Britons can attest to the fact that increasing the civil service by some 100,000 officials will, in the case of Brexit, expedite the withdrawal from a political and commercial federation. But this process is unable to mould the type of society, the type of sociality, and the resultant domestic political union. These are the bigger questions which received little penetrating attention in the Brexit conflict. Donald Trump’s withdrawal of America from global trading relations has been termed an American Brexit. Technically something along the lines of re-negotiating trading relations is possible, though the brutality and irrationality of Trump’s measures make clear no peaceful intent is meant.

Eighteenth century Scotland asked the big questions, because the developments in society, politics and trade were all novel. The Ricardian solution had not yet been imposed, which involved the ruthless overseas search for trading advantage and the creation of the market society. Commerce, for David Hume, should bring not just liberty but sociability, just as trade should spread civilization across the world. The debates at the time, however, pointed just as strongly in the other direction. England, and other colonising nations, should keep its wealth advantages to itself, and when faced with foreign competition should cut its domestic wages rather than graduate to higher level industries. Abroad, credit should fund a navy and armies, and in the competition for empire serfdom and slavery – the very opposites of liberty – were to become the dominant modes of production.

Another of Hume’s essays, ‘Of Public Credit’, today makes embarrassing reading and provokes the thought of just how egregiously the kingdom of Great Britain has projected itself since the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694. ‘The nation’, wrote Hume, ‘must destroy public credit, or public credit must destroy the nation’. William (of Orange) and Mary were founder shareholders in the Bank of England, and the English Parliament passed the legislation that tax revenue would cover all loans made to the crown in its never-ending war against the French monarchy and its claims to empire. Writing ‘Of Public Credit’ in 1752, a peace treaty had yet to be agreed with France (arriving in 1763). Britain had acquired not only a permanent navy and army but a permanent national debt in the form of scrip that could be traded and speculated on stock exchanges. ‘Our modern expedient is to mortgage the public revenues, and to trust that posterity will pay off the incumbrances ….’. ‘Drawing bills on posterity’ is a well-ventilated complaint, but anyone who owns the freehold on property will find taking out a mortgage, and paying it off, perfectly acceptable. Hume allows that public debt is the currency of traders ‘and this, it must be owned, is of some advantage to commerce, by diminishing its profits, promoting circulation, and encouraging industry’. States funding wars with debt is another matter completely. ‘According to modern policy war is attended with every destructive circumstance; loss of men, encrease of taxes, decay of commerce, dissipation of money, devastation by sea and land.’ A double speculation is involved, raising the debt in the first instance and then winning the war. Such a form of speculation affects the exchange of all commodities, the impact on the structure of debt the primary consideration. This detracts from the line of virtue: commerce, to sociality, to liberty.

Some of this will, perhaps, resonate with Stephen Miran’s ‘A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System’ of November 2024, which is an attempt to reverse the unsustainable accumulation of United States public debt and the extension of fiat money beyond any reasonable denominator of value. Tariffs and jealousy of trade, however, are hegemonic solutions not a new enlightened version of the international division of labour.

With Ricardo and English global ascendancy in the nineteenth century, the solution imposed was taken to mean that economics and politics were a perfect fit. This then becomes the dominant in political economy, and just as in Brexit so in Trumpland, the arguments against these misadventures are economistic in kind and assume the enduring affinity of trading markets, capitalism and modern representative government. In the same way the conventional wisdom before 1914 was that civilization had taken the liberal trading route and that the reciprocity between nations excluded the possibility of war. But this view was unable to perceive that the First World War was not a war between European neighbours but a war over imperial expansion and global power – a repeat of the 18th century. So, for Kaiser Wilhelm, after Europe was conquered the United States would fall under German rule. And, of course, for Britain there could be only one nation with a high seas fleet.

The same global rivalry had been on view in the era of colonial expansion starting in the seventeenth century. While Adam Smith is singled out as an economist who extolled economic activity and trade over war, that is not accurate. The reciprocity of trade would not lead to Kant’s perpetual peace, but to a new fusion of war and trade. Smith’s realism acknowledged the cohabitation of war with commerce. The enlightened approach was the endeavour to steer affairs in the direction of ‘good government and profitable trade’ (Hont 2005: 7).

This would not be easy. In Hume’s analysis the novelty of the situation was the coming together of the republican Italian state – seen as a first in terms of civic humanism – and the rise of commerce. Humanism opened the way of being able to think about society as one allowing sociability to take the place of rigid status inequality. Machiavelli figured in a double sense. His advice to the prince was to act tyrannically but with the illusion of integrity, but in his Discourse the prize was the realization of humanism under good government. The statecraft of the large European dynasties under the impetus of commerce was being developed in the same double-edged way.

Istvan Hont, in his remonstrating book, Jealousy of Trade, argues the issue was never settled; that is, until it was thought to be settled, in London, with Ricardo and the nineteenth century political economists. But this economism led to two centuries of a perpetual conflict that is etched into ‘our’ understanding of political economy. It is the conflict between liberalism and Marxism, each with their numerous variants. Seen in this light, ‘jealousy of trade’ is a perennial avoidance mechanism. In its simplest form, it is the refusal to trade, the refusal to modernize an economy, and the impossibility of giving up the traditional status order. Max Weber in his political writings took on the reactionary agrarian order in favour of modernization and democratization, of everything. But radical politics and revolution were never absent, and Weber – to say the least – was stretched to the limit in designing a politics that would combine a democratic federal union with the capitalist division of labour. Weber lived through a high point of global imperialism, whose advantages he acquiesced in faut de mieux. For him the eighteenth century, and its philosophy, was a pastoral adventure in comparison. The Scottish enlightenment does not feature in Weber’s copious writings on political economy, so illustrating Istvan Hont’s argument that liberalism as the exercise of freedom has to re-consider the coming together of commerce, the eighteenth century ‘national’ state, and republican humanism.

The Scottish enlightenment had set out the good and bad options. Commerce brings an international division of labour. This must be constructed as one that raises skills and arts in all countries to their mutual benefit. Under the right statecraft, commerce brings peace, and with commerce flourishes liberty. Sociability is the new basis of organizing society in place of neo-feudal hierarchy. Against this, the jealousy of trade carried the image of Machiavelli’s The Prince. His reappearance in the form of Donald Trump with a project worthy of a Medici prince, but without the guile, looks to be a catastrophe for the world.

Reference

Istvan Hont. 2005. Jealousy of Trade: International Competition and the Nation-State in Historical Perspective. Harvard University Press.